Using AI To Create Signature Frameworks That Make Your Expertise Memorable

The framework isn't the acronym. It's the system you observed working, made memorable.

When I started my career in design and tech, I was faced with staggering complexity. My breakthrough came when I learned about frameworks.

It happened during my early years of public speaking. A more experienced speaker gave me advice that has stuck with me ever since: “If you’re explaining something, always have a framework.” Frameworks became my compass, a lens to view and simplify problems, turning vague thoughts into clear, actionable strategies.

This changed not only how I approached public speaking but also how I thought about designing products, organizing information, and tackling complex challenges. Frameworks transformed confusion into coherence. They helped me align scattered ideas into something tangible, something I could act on and share with others.

Years later, I realized something else about frameworks: they’re not just tools for clarity. They’re intellectual property.

Think about the business experts you remember. Simon Sinek has “Start With Why.” Stephen Covey had “7 Habits.” Clayton Christensen had “Jobs to Be Done.” These frameworks aren’t just organizing tools for their own thinking. They’re what made their expertise memorable, shareable, and valuable. When you have a signature framework, people don’t just remember your advice. They remember you.

AI has made the packaging step faster. You can generate acronym options, test structures, and refine language in hours instead of months. But that speed has created a new problem: people are skipping the work that makes a framework worth building in the first place.

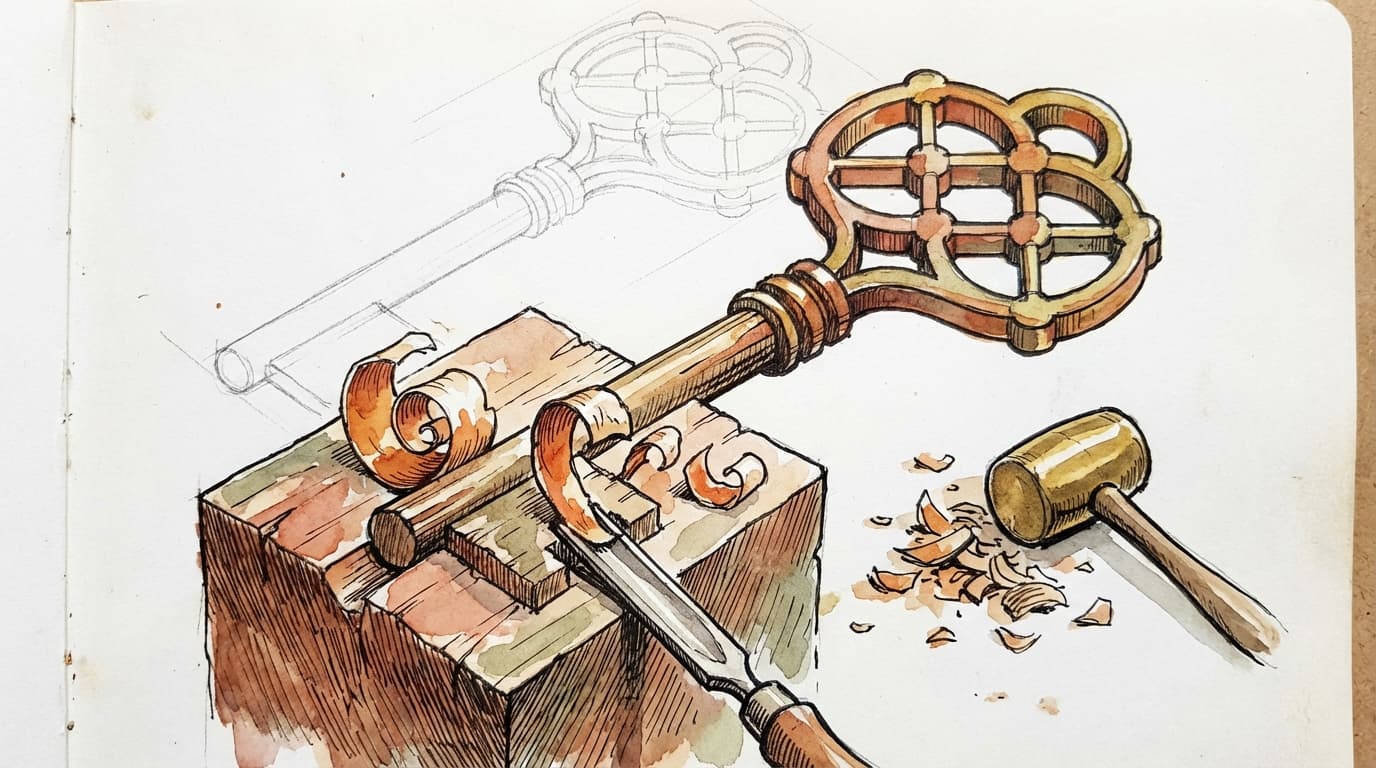

A framework isn’t a branding exercise. It’s a system you’ve already observed working, made easier to remember. The acronym is the last thing you create, not the first.

Frameworks Start With Systems

I talk a lot about this in the goal-setting workshops I do: the things that make things work are actually systems. A repeatable process that produces consistent results. That’s the raw material a framework is built from.

No one ever asked me what my process was for building frameworks before AI existed. And like many things I do, I probably never deeply thought about it until someone did. But it always starts the same way.

Observation. Pattern recognition. Documenting what I’m measuring and tracking along the way.

You notice that certain things keep working. You notice that when you skip a particular step, things fall apart. You notice that when you explain a concept a certain way, people get it immediately, and when you explain it another way, you lose them. Those observations accumulate. Eventually, you realize you’re looking at a system.

Once you identify the system, the framework is just the packaging that makes it easy to learn and memorable enough to stick. But the system has to exist first. Without it, you’re decorating an empty room.

How You Know Someone Skipped the Work

The easiest way to spot a framework built on nothing is to watch someone try to explain it or put it into practice.

They struggle to stay within their own structure. They force ideas into letters that don’t quite fit. They trip over step three because step three exists to complete the acronym, not because it represents something real.

Think about frameworks that actually work. OKRs have evidence behind them. There’s a process, and it’s easy to remember because the process is real. At any point, if someone asks you about the K in OKR, you can talk about Key Results on its own. You can explain what it means, why it matters, and how to do it well without ever referencing the acronym.

That’s the test. The letters or steps are functional components that help you remember the system. They are not the system itself. If you can explain every piece of your framework without the clever packaging and it still holds up, you have something real. If you can’t, you have a slide deck.

The Failure Mode: Cleverness Before Function

I’m a big metaphor and analogy person because I think that’s how people transfer knowledge best. So I’ve spent a lot of time trying to make ideas memorable. And the times it hasn’t worked follow the same pattern.

You come up with something clever before you have the steps properly identified. You fall in love with a word. Then you start rearranging your actual process to fit the letters. Step two and step four swap places because the acronym reads better that way, not because the sequence makes more sense. You add a component that doesn’t need to exist because you need a vowel.

Now your framework looks great on paper, but when you try to teach it, you’re fighting your own structure. That’s how you end up in failure mode. You optimized for memorability at the expense of accuracy, and a framework that doesn’t accurately represent how something works is worse than no framework at all. It’s confidently wrong.

Where AI Actually Fits

This is where people get tripped up. AI is genuinely useful for framework development. But it’s useful at a specific point in the process, not at the beginning.

Here’s the sequence that actually works:

Observation and pattern recognition. This is yours. You notice what works, what fails, what repeats. You document it. You test it in practice. No AI involved yet.

Identifying the system. You distill your observations into the core components. What are the 3-7 elements that actually make this work? You write them in plain language. Still no AI.

Validating the system. Can you explain each component on its own? Does the sequence hold up? Have you tested this with real people in real situations? This is where most of the work lives. Still no AI.

Packaging the system. Now AI helps. You have real components backed by real experience. You need a memorable structure. AI can generate acronym options, suggest sequential models, propose analogies, and help you find language that sticks. This used to take weeks of iteration. Now it takes hours.

Pressure-testing the package. AI can also help here. Ask it to poke holes. “What’s missing? What’s redundant? What would confuse someone encountering this for the first time?” Then apply your own judgment to the answers.

The ratio matters. Roughly 80% of the work is the first three steps. The last two steps are where AI accelerates things. If you flip that ratio and start with AI, you get a polished acronym wrapped around nothing.

Building Frameworks With AI (After You’ve Done the Work)

Once you have your system identified and validated, here’s how to use AI as a packaging partner:

Structure exploration. Give AI your core components and ask for multiple structural options:

“I have [number] key components for [your topic]: [list your components]. Generate framework concepts using these approaches: five possible acronyms, a sequential process model, a category-based structure, and a visual metaphor. My audience is [describe who you’re teaching]. Keep it practical and memorable.”

Refinement. Pick the structure that feels most natural and iterate: “What if this was four components instead of five? What if I organized these by sequence instead of category?”

Gap analysis. Use AI to stress-test: “Review this framework. Are there critical aspects that aren’t addressed? What might someone miss if they only followed these steps?”

The final gut check is yours. Does this sound like you? Would you naturally reference this in conversation, or does it feel forced? Is it accurate to your experience? If you find yourself explaining around your own framework, the structure isn’t right.

How I Created the GUIDE Framework

Let me show you this process in practice. When I developed the GUIDE framework for AI ethics, it didn’t start with AI or with the word GUIDE.

It started with building Hello Alice’s AI policy and navigating SOC 2 compliance. Through that work, I kept running into the same five areas that mattered: governance and accountability, understanding bias and impact, transparency, data privacy, and stakeholder engagement.

Those weren’t theoretical categories. They were the things that actually came up, repeatedly, in real implementation. I could talk about any one of them at length because I’d lived through the problems they solve.

Only after I had those five components validated through practice did I bring AI into the process. I gave it the components and asked for acronym options. GUIDE stood out because it connected naturally to the concept of providing guidance. It wasn’t forced. The letters mapped to the real components without rearranging anything.

That’s what the process looks like when the system comes first.

Types of Frameworks to Consider

When you’re ready to package your system, these are the most common and effective structures:

- Acronyms create a word where each letter stands for a key component. SMART goals, my GUIDE framework for AI ethics. These work best when the components are distinct and the acronym connects to the overall concept.

- Sequential processes organize ideas into steps or stages. Design Thinking (Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, Test), my ACTOR framework for prompting. These work best when order matters.

- Categories or lenses organize concepts into distinct types or perspectives. The Four Ps of Marketing, my Three A’s of AI (Automation, Augmentation, Autonomy). These work best when you’re helping people see different facets of the same topic.

- Analogies or metaphors compare your concept to something familiar. The iceberg model for organizational culture. These work best when you’re making abstract concepts tangible.

- Visual models show relationships between elements. Venn diagrams, quadrant models like the BCG Matrix. These work best when overlap or tension between concepts is the point.

The best structure depends on what you’re teaching and how the system actually works. Don’t pick a type first and force your content into it. Let the system tell you what structure it needs.

Kenzie Notes

Analog wisdom for a digital world

A weekly page from The Workshop — frameworks, stories, and practical thinking on leadership, systems, and the craft of building things that matter. Wednesdays.